The explicit reason was to swiftly end the war with Japan. But it was also intended to send a message to the Soviets.

Updated: August 1, 2024 | Original: July 21, 2020

Ever since America dropped a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki, Japan on August 9, 1945, the question has persisted: Was that magnitude of death and destruction really needed to end World War II?

A few days earlier, just 16 hours after the U.S. B-29 bomber Enola Gay shocked the world by dropping the first A-bomb known as “Little Boy” on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, the White House issued a statement from President Harry S. Truman.

Atomic Bomb HistoryIn addition to introducing the world to the previously top-secret atomic research program known as the Manhattan Project, Truman doubled down on the threat that nuclear weapons posed to Japan, America’s only remaining adversary in the war. If the Japanese did not accept the terms of unconditional surrender drafted by Allied leaders in the Potsdam Declaration, Truman wrote, “they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.”

But even as Truman issued his statement, a second atomic attack was already in the works. According to an order drafted in late July by Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, director of the Manhattan Project, the president had authorized the dropping of additional bombs on the Japanese cities of Kokura (present-day Kitakyushu), Niigata and Nagasaki as soon as the weather permitted.

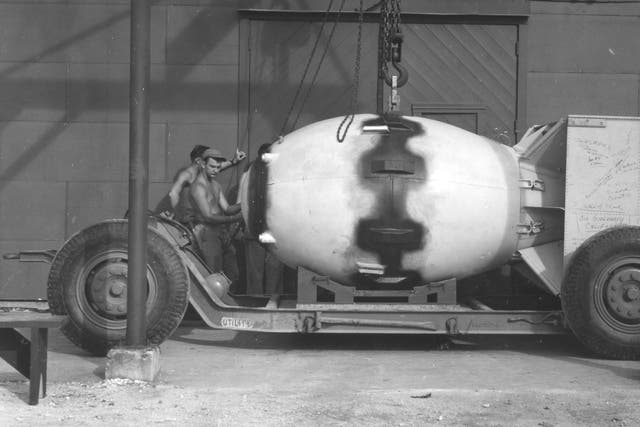

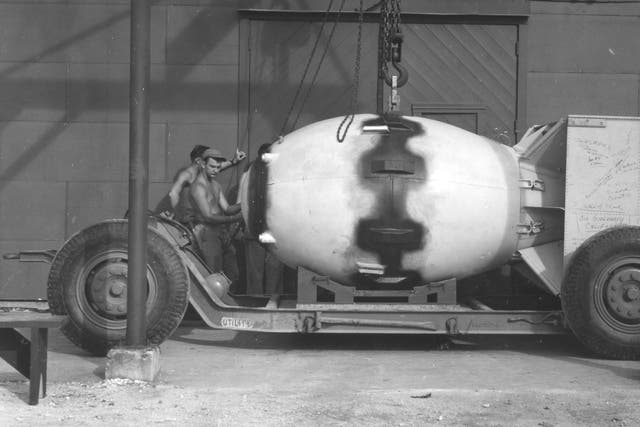

Early on the morning of August 9, 1945, the B-29 known as Bockscar took off from Tinian Island in the western Pacific Ocean, carrying the nearly 10,000-pound plutonium-based bomb known as “Fat Man” toward Kokura, home to a large Japanese arsenal. Finding Kokura obscured by cloud cover, the Bockscar’s crew decided to head to their secondary target, Nagasaki.

“Fat Man,” which detonated at 11:02 local time at an altitude of 1,650 feet, killed about half as many people in Nagasaki as the uranium-based “Little Boy” had in Hiroshima three days earlier—despite a force estimated at 21 kilotons, or 40 percent greater. Still, the effect was devastating: close to 40,000 people were killed instantly, and a third of the city was destroyed.

“This second demonstration of the power of the atomic bomb apparently threw Tokyo into a panic, for the next morning brought the first indication that the Japanese Empire was ready to surrender,” Truman later wrote in his memoirs. On August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s unconditional surrender, bringing World War II to a close.

Before the 1945 atomic blasts, they were thriving cities. In a flash, they became desolate wastelands.

As the fateful bombing mission commenced half a world away, the anxious president waited for news at sea in the Atlantic.

The colossal power of the atomic bomb drove the world’s two leading superpowers into a new confrontation.

According to Truman and others in his administration, the use of the atomic bomb was intended to cut the war in the Pacific short, avoiding a U.S. invasion of Japan and saving hundreds of thousands of American lives.

In early 1947, when urged to respond to growing criticism over the use of the atomic bomb, Secretary of War Henry Stimson wrote in Harper’s Magazine that by July 1945 there had been no sign of “any weakening in the Japanese determination to fight rather than accept unconditional surrender.” Meanwhile, the U.S. was planning to ramp up its sea and air blockade of Japan, increase strategic air bombings and launch an invasion of the Japanese home island that November.

“We estimated that if we should be forced to carry this plan to its conclusion, the major fighting would not end until the latter part of 1946, at the earliest,” Stimson wrote. “I was informed that such operations might be expected to cost over a million casualties, to American forces alone.”

Despite the arguments of Stimson and others, historians have long debated whether the United States was justified in using the atomic bomb in Japan at all—let alone twice. Various military and civilian officials have said publicly that the bombings weren’t a military necessity. Japanese leaders knew they were beaten even before Hiroshima, as Secretary of State James F. Byrnes argued on August 29, 1945, and had reached out to the Soviets to see if they would mediate in possible peace negotiations. Even the famously hawkish General Curtis LeMay told the press in September 1945 that “the atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all.”

Statements like these have led historians such as Gar Alperovitz, author of The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb, to suggest that the bomb’s true purpose was to get the upper hand over the Soviet Union. According to this line of thinking, the United States deployed the plutonium bomb on Nagasaki to make clear the strength of its nuclear arsenal, ensuring the nation’s supremacy in the global power hierarchy.

Others have argued that both attacks were simply an experiment, to see how well the two types of atomic weapons developed by the Manhattan Project worked. Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, commander of the U.S. Navy’s Third Fleet, claimed in 1946 that the first atomic bomb was “an unnecessary experiment…[the scientists] had this toy and they wanted to try it out, so they dropped it.”

Was a second nuclear attack necessary to force Japan’s surrender? The world may never know. For his part, Truman doesn’t seem to have wavered in his conviction that the attacks were justified—though he ruled out future bomb attacks without his express order the day after Nagasaki. "It was a terrible decision. But I made it,” the 33rd president later wrote to his sister, Mary. “I made it to save 250,000 boys from the United States, and I'd make it again under similar circumstances.”

Stream World War II series and specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault.